Limiting popular sire phenomenon

A recent study, published a few weeks ago, investigated measures that can be used to limit genetic erosion within dog breeds, using simulation of the dutch Golden retriever population. It is not the first time that the main author, Jack Winding, interests himself on questions around management of genetic variability in dogs. He wrote among others with Kor Oldenbroek a book on dog breeding (in Dutch), and build also an interesting monitoring tool for kennel clubs interested in the management of genetic variability. This last article aimed at assessing efficiency of the measures that can be taken by breed clubs to limit the increase of inbreeding over time in their breeds.

Before talking about the result of this study, it appears important to remind what are the factors involved in the erosion of within population variability.

- First, genetic variability within a given population is basically related to the number of reproducers used at each generation. It may be easily understand that in a population where less than 10 sire or dams are used each generation, the chance of inbreeding will occur much quickly in comparison to another population with 1000 reproducers.

- Not independently, the disequilibrium in the use of reproducers may also lead to increased genetic erosion. Even if you count several hundreds of reproducers within a given population, if 50% of the mating is made by 2 or 3 sires, diversity is going also to fall quickly. This means also that sex ratio is important for the management of genetic variability, and it has been showed that genetic variability will be better preserved in a population with 20 sires and 100 dams, than with a population with 10 sires and 10,000 dams.

- The choice of the individuals to be used as reproducers is also very important, and you may use as many sires and dams you want, if in the next generations the reproducers are chosen among the offspring of only a couple of them, you may expect a strong genetic erosion in a few generation.

- Finally, the generation interval is also a parameter to be considered, as inbreeding increase over time will be all the more quick since reproducers are rapidly replaced by their offspring.

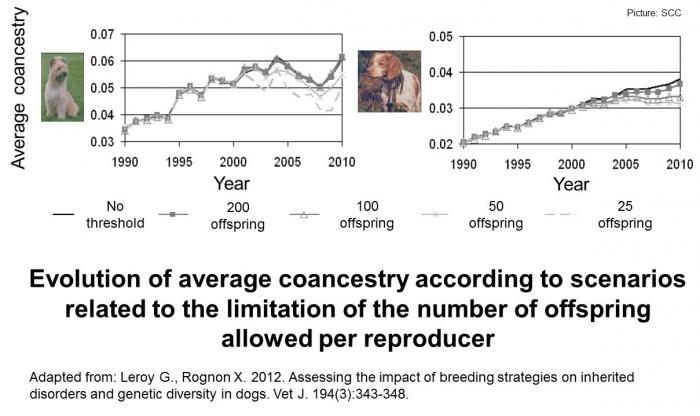

So, just suppose you have a limited number of reproducers: to limit genetic erosion as far as possible within the population, 50% of those reproducers should be males and 50% female, each of them should have one offspring male and one female used as reproducers, and those replacement offspring should be produced as late as possible. Of course, such measures may be very binding for breeders, removing a lot of the interest of breeding. It appears therefore of paramount interest that kennel clubs propose breeding rules allowing an efficient management of genetic variability, without restricting too much the choices of breeders. A classical measure is to limit the number of litters authorized for a given reproducer, which is recommended by FCI breeding rules and applied in countries like Finland, where this option is included in national health PEVISA programmes. In an early publication on similar topic (Leroy and Rognon 2012), we showed the impact that the limitation of the number of offspring per reproducer could have on genetic variability, as illustrated below.

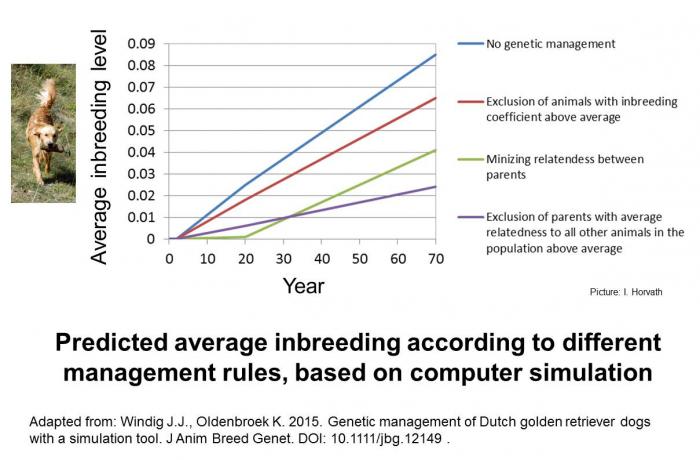

Other measures can be imagined, aiming at increasing the number of reproducers used, limiting the number of offspring allowed to breed per reproducers (focusing on males as they use is generally more intensified than females), or restricting the relatedness of potential reproducers within each other or with the current generation. In their article, Windig and Oldenbroek tested those different strategies on a population simulated, showing that the best strategies were related to the limitation of the use of popular sire, and to the restriction of breeding to parents with low relatedness to the population. By contrast, approaches aiming at limiting the inbreeding of reproducers themselves or relatedness between parents to be mated were found less efficient. Relative to the use of the threshold to limit the number of litter per sire, it was showed in the study that it was more efficient to consider a fixed number of litters per year than per reproductive life, as the replacement of sire may lead to a reduction of generation interval, which may reduce the impact of the measure. Also, choosing less related reproducers to be mated has only short term effect on inbreeding. For improving management of breed diversity, it appear better to choose reproducer as less related as possible to the current population.

These guidelines are of clear interest for dog clubs aiming at implementing breeding strategies for the management of within-breed genetic variability. Of course, some practical questions remain, such as the thresholds to be chosen for a given breed, once a given measure has been decided. In our early publication, we showed that the same threshold recommended by FCI (the number of offspring per dog should not be >5% of the number of puppies registered in the breed population during a 5 year period) could be not applicable in some dog breeds with large population size, as this threshold was already higher than the maximum number of puppies per reproducer observed (for instance the FCI threshold was found to be equal to 1366 puppies in Epagneul breton), and probably too binding in some small breeds. In Braque Saint Germain breed, for instance the FCI threshold was found to be 14 puppies, meaning than dogs should not be able to produce no more than 2-3 litters to respect the recommendation. This illustrates the difficulty to find a general rule and the necessity to develop threshold specific for each breeds. In that aspect, the simulation program proposed by Windig and Oldenbroek can be very useful.

Of course, simulation approaches are not without weakness, as any simulation process is based on simplification hypothesis. For instance, it was not taken into account here that in real genealogies, pedigree knowledge is not the same for any individual, and a policy aiming at choosing reproducers unrelated to the current population, may actually favor the use of dogs with no pedigree. Strategies considering genealogical relatedness (coancestry, kinship…) should therefore take into account this difference, on one way or another. It should be also interesting to see how the use of original reproducers could be supported at the expense of those who are more related to the current population (i.e. from more famous origins), which is clearly against the usual practices in dog breeding... This kind of measure would therefore need a lot of communication with breeders, to explain issues at stake, but may be necessary, especially for breeds with limited population size.

References

- Leroy G., Rognon X. 2012. Assessing the impact of breeding strategies on inherited disorders and genetic diversity in dogs. Vet J. 194(3):343-348.

- Windig J.J., Oldenbroek K. 2015. Genetic management of Dutch golden retriever dogs with a simulation tool. J Anim Breed Genet. DOI: 10.1111/jbg.12149 .

Credit picture: I. Horvath, SCC

Recommended Comments