Selection on complex traits in dogs

As in other domestic species, a large number of traits of selective interest are of complex inheritance, meaning the phenotype expressed by a given individual is determined by an undetermined number of genes, and more or less impacted by its environment. The efficiency of a selection programme on those traits is depending on several factors, including the heritability of the trait, i.e. the part of phenotypic variation which can be related to genetic variation. In livestock species, statistical approaches have been developed and are used to provide estimated breeding values (EBVs), i.e. estimates of the genetic level of an animal, regarding a specific trait. For this, phenotypic measures are taken and combined among related animals to differentiate impact of genes from effect of environment.

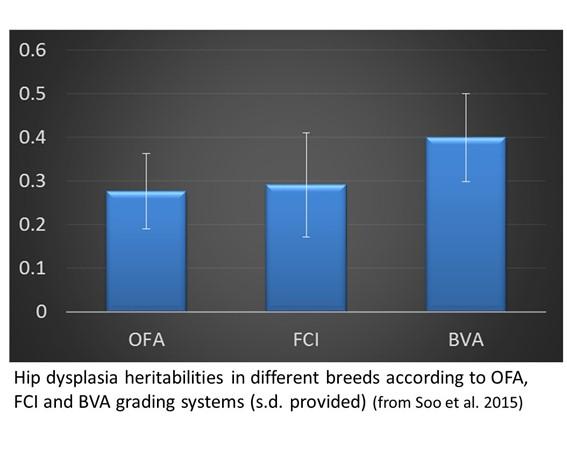

In dogs, a classical example of complex trait is the extent of hip dysplasia, probably the most common disorder within the species, with incidence above 10% in 45% of breeds according to OFA. A recent literature review of Soo and Worth (2015) investigated the diagnosis and approaches against hip dysplasia across the world. Currently three radiographic schemes are used as clinical diagnosis, namely the FCI one (based on the objective measurement of subluxation using the Norberg angle) in Europe, the BVA (British Veterinary Association) one in UK, and the OFA one in USA, based on subjective criteria. The figure below provides estimates of heritabilities reported in the above study. Whatever the system chosen, heritabilites have been estimated above 0.15 in most breeds, indicating that adequate breeding programmes should improve the status of breeds relative to hip dysplasia.

What about efficiency of breeding programmes and EBVs?

Despite the fact some EBVs have been already developed a long time ago in Germany for the German shepherd dog, most of the selection has been based until now on the basis of radiographic screening, i.e. the phenotype of the dogs. Different retrospective studies have observed only limited progress over the last years, despite more than 40 years of screening. Using the OFA data base, Hou et al. (2013) estimated that between 1989-2003, a limited genetic improvement has been observed, equivalent to 16.4% of the phenotypic standard deviation. For the UK, Lewis et al. (2010) has observed a 13% improvement in hip scores over the 10-year study period. However, pre-screening by owners, effectively removing information from the worst-affected animals and resulting in only better radiographs being shared/ recorded, has been viewed as a strong bias, being one of the main factors incriminated for such a limited progress. [Editor's note: this is less of a problem in registries where hip dypslasia screening is mandatory for all dogs used in breeding, e.g. Sweden and Finland. See link below.)]

This has led specialists to recommend the use of EBVs instead of phenotypic evaluation solely, as the EBV allows a more accurate identification of dogs with more healthy genetic status. Different studies (Lewis et al. 2010, Malm et al. 2013) has estimated that a selection based on EBVs should improve the genetic progress on hip dysplasia by around 20%. Consequently, in the last years, several countries such as Sweden and UK have proceeded to the implementation of EBVs in their breeding scheme. In that extent, the recent blog post of Katarina Mäki on the genetic progress against hip dysplasia since the implementation of EBV in Finland in 2002 is quite instructive.

And other traits?

Hip dysplasia is certainly not the only trait for which EBVs could have some use. For elbow dysplasia, for instance, EBVs are also computed in the Mate Select tool of UK Kennel club. The recent study of Lappalainen et al. (2015) on intervertebral disc calcification in Dachshunds in Finland provides another interesting example of this. With heritability around 0.5, there is clear indication of potential genetic progress on the trait, the improvement over the last years having been limited, in relation to the fact that only 10% of dogs have screening. It appears that the Finnish Kennel Club hopes to develop EBV on the disease for its breeders, which may be expected to increase the genetic progress relative to this disease.

Regarding behavioural traits, use of EBVs could be a way to improve the selection of dogs. However, as underlined in a previous post, the generally low heritability of those traits, rarely higher than 15%, may constitute a serious limitation to genetic progress.

And in the future?

Of course, one important opportunity in the future is related to the use of genomic information in relation to complex traits. In livestock species, a growing number of traits, usually estimated through classical EBVs, are now estimated through genomic selection, largely improving accuracy. This requires however a large reference population and a good knowledge of the genome of the species. Taking the example of hip dysplasia, several candidate genes have been identified with potential impact on hip dysplasia (Soo et al. 2015). In the future, it may be expected that genomic information could be used either to support classical EBV estimation (marker-assisted selection) or even replacing it (genomic selection). This would allow, among other benefits, to provide an estimate of breeding values at an earlier age, differentiating litter mates based on their respective genome. The technic would however need further improvement before any implementation.

References

Hou, Y., Wang, Y., Xuemei Lu, X., Zhang, X., Zhao, Q., Todhunter, R. J., & Zhang, Z. (2013). Monitoring hip and elbow dysplasia achieved modest genetic improvement of 74 dog breeds over 40 Years in USA. PloS one, 8(10), e76390.

Lappalainen, A. K., Mäki, K., & Laitinen-Vapaavuori, O. (2015). Estimate of heritability and genetic trend of intervertebral disc calcification in Dachshunds in Finland. Acta Veterinaria Scandinavica, 57(1), 1-6.

Lewis, T. W., Blott, S. C., & Woolliams, J. A. (2013). Comparative analyses of genetic trends and prospects for selection against hip and elbow dysplasia in 15 UK dog breeds. BMC genetics, 14(1), 16.

Malm S, Sørensen AC, Fikse WF, Strandberg E. (2013) Efficient selection against categorically scored hip dysplasia in dogs is possible using best linear unbiased prediction and optimum contribution selection: a simulation study. Journal of Animal Breeding and Genetics 130, 154–64.

Soo, M., Sneddon, N. W., Lopez-Villalobos, N., & Worth, A. J. (2015). Genetic evaluation of the total hip score of four populous breeds of dog, as recorded by the New Zealand Veterinary Association Hip Dysplasia Scheme (1991–2011).New Zealand veterinary journal, 63(2), 79-85.

Wilson, B. J., Nicholas, F. W., James, J. W., Wade, C. M., Tammen, I., Raadsma, H. W., ... & Thomson, P. C. (2012). Heritability and phenotypic variation of canine hip dysplasia radiographic traits in a cohort of Australian German shepherd dogs. PloS one, 7(6), e39620.

Recommended Comments