When dog looks like a star: the purebred paradigm

Contrary to what could imply the title, instead of dealing with dog shows, in this post I will talk about population genetics...

With development of genomics in the last fifteen years, population geneticists have been able to study the genetic structure of domestic species, investigating among other things the genetic relationships among breeds. Phylogenetic trees constitutes classical tool used for representing such relationships graphically. However those tree assume that once lineages have diverged, no cross may ever occur, which is obviously untrue when considering domestic populations. Alternate graphical representations have therefore been developed such as neighbornet network, which consider all possible relationships among breeds. It appears interesting to compare the results that have been found depending on the species considered (knowing however that those results also depend on the breeds included within the analysis).

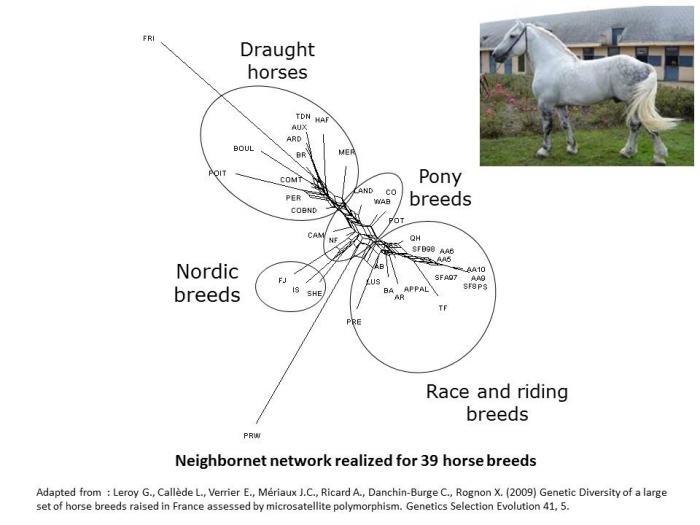

In horse for instance (Leroy et al. 2009), some analysis have clustered horse breeds mainly according to their use, with a differentiation from heavy horses to race and riding breeds, pony breeds being found intermediate.

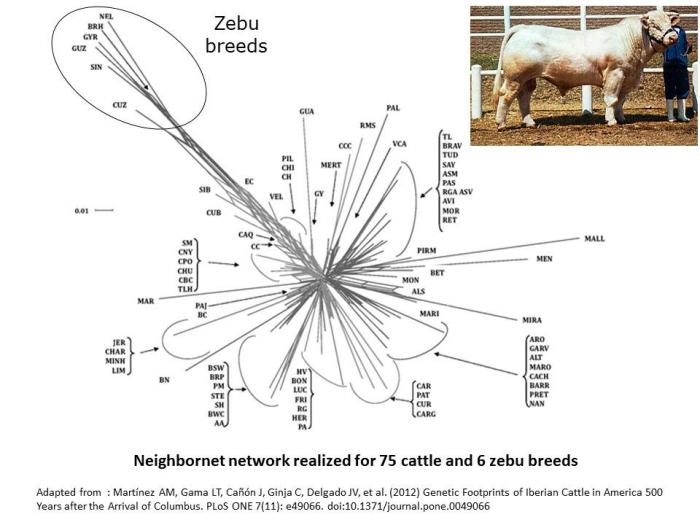

By comparison, neighbornet network in cattle are shaped by the differentiation between European cattle and Zebu breeds (Martinez et al. 2012).

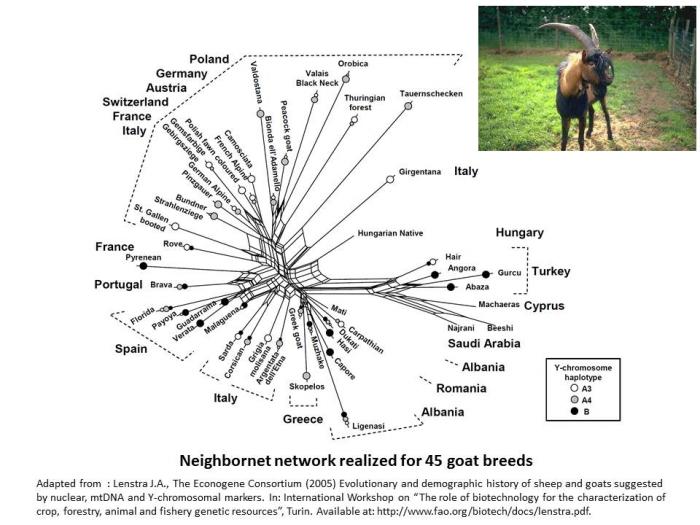

In goat species also, it appears the genetic differentiation is based on the genetic origin of breeds (Lenstra et al. 2005).

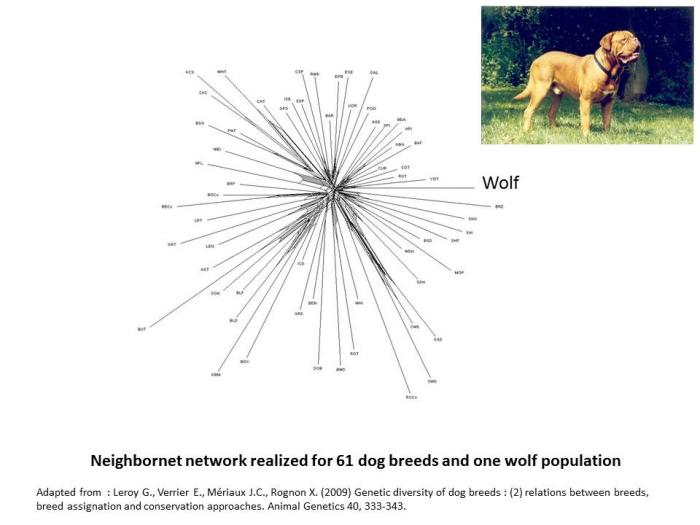

When considering dog the situation, phylogenetic networks appear shaped like a kind of star (Leroy et al. 2009). This star-like pattern could suggest that in dog, breeds emerged from an undifferentiated gene pool. This is obviously untrue: dog types existed largely before the standardization of breeds in the 19th century, and other studies have been able to underline closer genetic relationships existing among herding dogs, mastiff like dogs or spaniels for instance (VonHoldt et al. 2012). More likely, this particular shape underlines that genetic differentiation at the breed level is more emphasized in dog, in relation to the fact that, more than in any other species, purebreeding is considered as a paradigm. As a consequence, amount of geneflows accross breeds is in general very limited in dog, especially in comparison to other domestic animals.

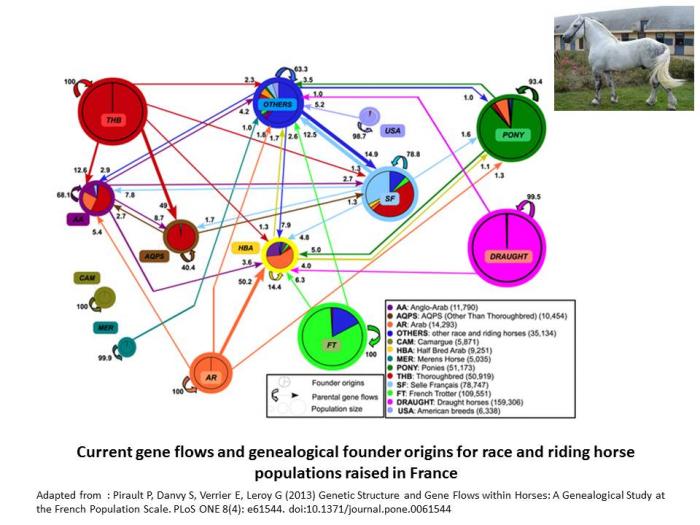

Indeed, in cattle, improvement of genetic trait has favored introgression from the more productive breeds to improve the performance of other populations, and for instance, the Hostein breed has been used all around the world to improve local dairy breeds. In horses, gene flows are frequent and regular across breeds, as illustrated below (Pirault et al. 2013). Even in cats, a large part of the breeds are actually varieties which are intercrossed.

The limited amount of geneflows, combined with important prolificacy in dog species and relative short generation intervals (around 4 year), have probably led to important founder effects in dog breeds, explaining the genetic structure observed at the specie level. The problem is that, while on the one hand, purebreeding is one of the bases of modern selection, whatever the species, on the other hand, excluding any form of introgression can be damageable, especially for the purpose of management of genetic variability. Indeed, genetic bottlenecks related to this strong founder effect reduces the genetic basis of each breed, increasing the risks linked to inbreeding and dissemination of inherited disorders.

In the cases when some group of breeders decides to undertake a crossbreeding programme, such initiative is often view as controversial by other breeders. Of course, crossbreeding should not be decided by anybody, but on the other hand, it is rather unclear at which level the decision should be taken: by the local kennel club, by the kennel club of the country of origin, by the FCI? Also, until now, there has been a lack of studies investigating when, and how, crossbreeding should be used. This will be the subject of another post.

References:

- Lenstra J.A., The Econogene Consortium (2005) Evolutionary and demographic history of sheep and goats suggested by nuclear, mtDNA and Y-chromosomal markers. In: International Workshop on “The role of biotechnology for the characterization of crop, forestry, animal and fishery genetic resources”, Turin. Available at: http://www.fao.org/biotech/docs/lenstra.pdf.

- Leroy G., Callède L., Verrier E., Mériaux J.C., Ricard A., Danchin-Burge C., Rognon X. (2009) Genetic Diversity of a large set of horse breeds raised in France assessed by microsatellite polymorphism. Genetics Selection Evolution 41, 5.

- Leroy G., Verrier E., Mériaux J.C., Rognon X. (2009) Genetic diversity of dog breeds : (2) relations between breeds, breed assignation and conservation approaches. Animal Genetics 40, 333-343.

- Martínez AM, Gama LT, Cañón J, Ginja C, Delgado JV, et al. (2012) Genetic Footprints of Iberian Cattle in America 500 Years after the Arrival of Columbus. PLoS ONE 7(11): e49066. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0049066.

- Pirault P, Danvy S, Verrier E, Leroy G (2013) Genetic Structure and Gene Flows within Horses: A Genealogical Study at the French Population Scale. PLoS ONE 8(4): e61544. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0061544.

- Volholdt B.M., Pollinger J.P. Lohmueller K.E. Han E. et al. (2010) Genome-wide SNP and haplotype analyses reveal a rich history underlying dog domestication. Nature 464(7290):898-902.

Credit picture: I. Horvath / SCC / AgroParisTech

Recommended Comments