Kennel Club Breed Population Analyses tool

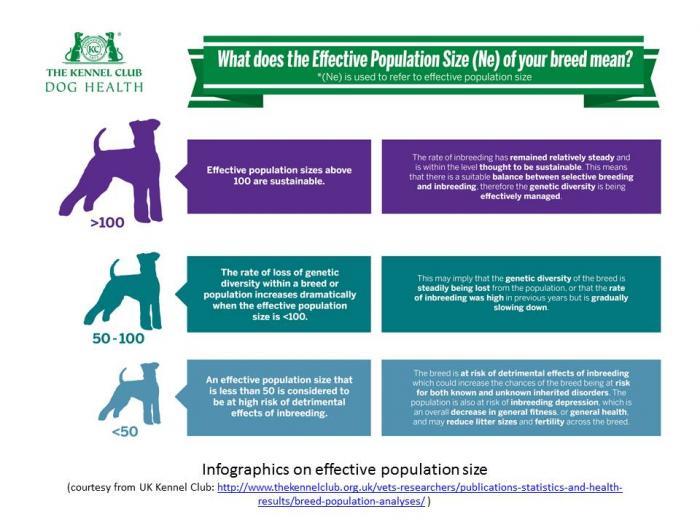

A few weeks ago, Tom Lewis and his colleagues published what is, up to now, the largest pedigree analysis regarding to the number of populations analyzed, with the 215 breeds recognized by the UK Kennel Club. In the same time, individual breed reports have been made available in the KC website, with accessible infographics on the phenomena behind inbreeding such as effective population size or popular sire effect. Just for this, this work should be saluted, and we can hope that other national kennel clubs will follow this example. Actually, even people most critical to the KC breeding policy have recognized that it should be congratulated for this study. Yet it has also been stated that the global message of the paper, indicating that “initial excessive loss of genetic diversity has latterly fallen to sustainable levels” was probably too much optimistic. After all, it can be indeed considered that 25% of breeds with effective population size under 50 is not so sustainable.

A few weeks ago, Tom Lewis and his colleagues published what is, up to now, the largest pedigree analysis regarding to the number of populations analyzed, with the 215 breeds recognized by the UK Kennel Club. In the same time, individual breed reports have been made available in the KC website, with accessible infographics on the phenomena behind inbreeding such as effective population size or popular sire effect. Just for this, this work should be saluted, and we can hope that other national kennel clubs will follow this example. Actually, even people most critical to the KC breeding policy have recognized that it should be congratulated for this study. Yet it has also been stated that the global message of the paper, indicating that “initial excessive loss of genetic diversity has latterly fallen to sustainable levels” was probably too much optimistic. After all, it can be indeed considered that 25% of breeds with effective population size under 50 is not so sustainable.

Is it so? And actually what can be deduced from the paper and the analysis?

Evolution of inbreeding

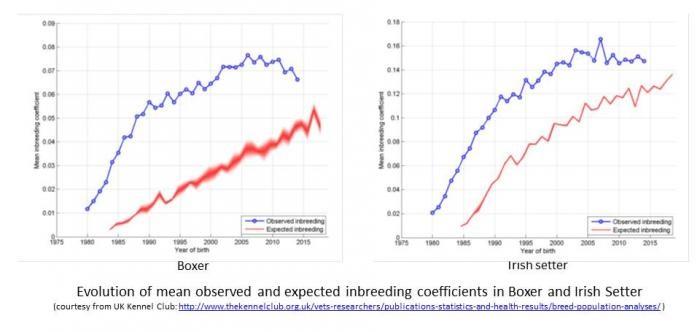

From far away, the most striking result is related to this stabilization (and in several case decrease) of inbreeding occurring in most breeds since the years 2000. As a consequence when computed on recent years, effective population size have increased in multiple breeds. Actually, in case when inbreeding was decreasing, it was not even possible to compute effective population size. But does this really mean that inbreeding stopped to increase? Probably not. First because, in theory, inbreeding can only increase. As the number of generations increases, more and more ancestors in common between both parents will be found, adding their contribution to overall inbreeding. Therefore, as underlined by the authors, this change in inbreeding trend is probably largely explained by the fact that importation increased largely in the years 2000, after relaxation of UK quarantine law. This has probably led to the registration of foreign dogs, with limited pedigree knowledge, and therefore supposedly unrelated. In practice, it is certain that on the beginning, those dogs were less related that the average of national dogs. Yet, after a few years of importations, it is also probable that imported dogs are actually bringing more inbreeding that what is hypothesized based on their limited pedigree knowledge. It could therefore have been interesting to correct genetic parameters such as effective population size by considering this pedigree knowledge.

But is this so simple? Actually, the study of Lewis also provides some results indicating that the recent evolution of inbreeding could be also linked to real inbreeding reduction, although temporary. Indeed, inbreeding is the sum of the reduction of within population genetic variability (which can only decrease), added to factors inherent to the population, such as existence of subpopulations, or mating between close relatives. The extent of inbreeding due to population structure can be assessed by comparing population inbreeding with the degree of coancestry between individuals, or between their parents. This is what Lewis and his colleagues have done, when referring to expected inbreeding. In most of their breeds, real observed inbreeding appears larger than expected one, indicating existence of substructure. Yet in the majority of cases, this difference has clearly decreased over the last years, which probably indicates that breeders have improved their breeding practice, eventually toward less mating between close relatives.

Reduction of popular sire phenomenon

One of the interrogations that I have with this paper is related to the fact that they may have been some change in the use of popular sires. Indeed, a more balanced use of reproducers is expected to reduce (but not inverse) the increase of inbreeding. However, as previously stated, it is difficult to identify such tendency on the basis of inbreeding evolution alone, as it is already impacted by importations and change of substructure. As suggested by the authors, the analysis of the progeny distribution overtime may bring some information on this issue. Yet it has to be stated that this distribution is highly dependent on breed demographics: in a population with 100 annual births, it is quite easy to have a sire producing 25% of the puppies; it is hardly possible in a population with 10,000 births. In most of the breeds studied, registration have either largely increased or decreased over years, so the direct interpretation of progeny distribution evolution should only be made in breeds with stable registrations. Eventually a statistical analysis of the results over the 215 breeds could bring interesting results on this evolution.

So, on my point of view, if there is still effort to be made in the management of genetic variability within UK dog breeds, the article point out some clear progress. Increased importation probably brought some variability within national population, even if those improvements should not be overestimated: imported dogs of yesterday are probably related to imported dogs of today. They have been also probable improvements in mating practice, which is also good news. It is rather difficult for me to identify if there has been change in popular sire phenomenon, and further analysis could bring information on this. In term of communication, it is highly appreciable that messages on better management are brought to the breeders.

References:

Lewis T.W., Abhayaratne B.M., Blott S.C. (2015) Trends in genetic diversity for all Kennel Club registered pedigree dog breeds.Canine Genetics and Epidemiology20152:13

DOI: 10.1186/s40575-015-0027-4

Credit picture: I. Horvath

Donate

Donate

4 Comments

Recommended Comments