Extreme phenotype: ways to handle it?

Selection on exaggerated morphological features is probably one of the most important problem facing purebred dogs, one of the difficulties being to identify precisely how those morphological traits are affecting the health of the dogs. The recent study of Packer et al. (2015) however provides a very interesting example and suggestions on what could be done relative to the brachycephalic issue.

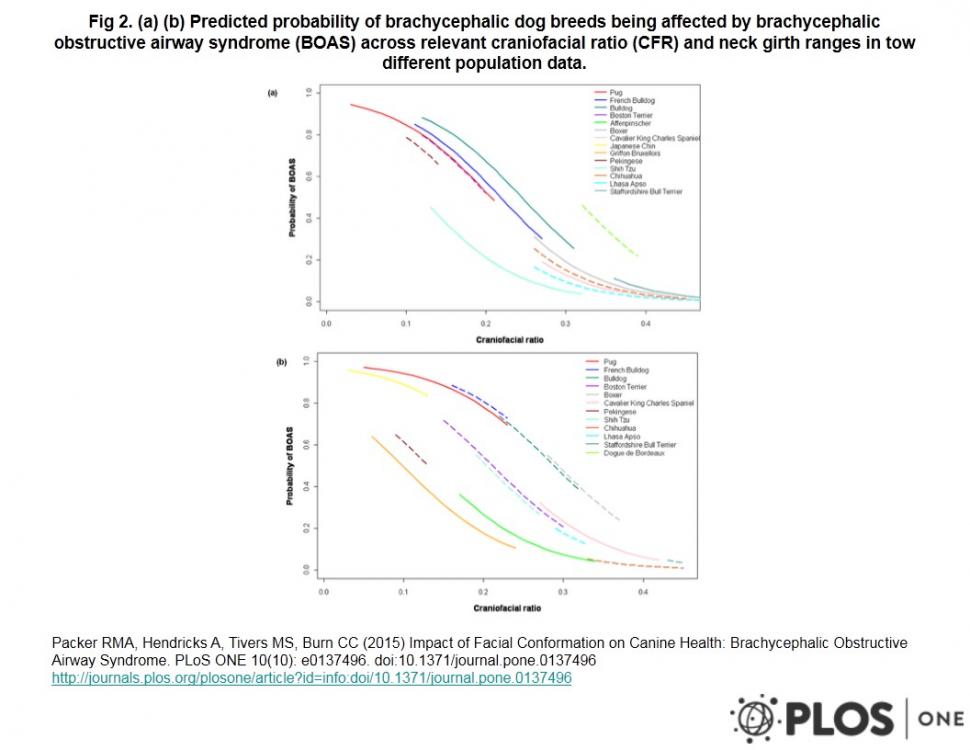

It indeed illustrates nicely how Brachycephalic Obstructive Airway Syndrome (BOAS), a chronic debilitating syndrome seen frequently in brachycephalic dogs, is connected, in a non-linear manner, with the shortening of muzzle length. According to this study BOAS occurred only in dogs whose muzzle length was less than half the cranial length. A majority of dogs which had this craniofacial ratio lower than 0.2 were found to be affected. The study found also that thick neck girth, obesity and neutering increased the risk for BOAS.

With this craniofacial ratio, breed clubs now have a good indicator that could be used to reduce the incidence of this condition. It is clear that some good work could be made through the promotion of dogs with longer muzzle or even, inserting some condition on this ratio into the standard. As shown in the article, for some breeds, such as the Japanese Chin, it would probably be difficult to improve this ratio to needed values relative to BOAS but efforts have to be made any way, using crossbreeding if necessary. If stakeholders from the dog world do not move on this, it is clear that, at some point, some one else will, and it won’t necessarily be for the good of their breeds.

References:

Asher, L., Diesel, G., Summers, J. F., McGreevy, P. D., & Collins, L. M. (2009). Inherited defects in pedigree dogs. Part 1: Disorders related to breed standards. The Veterinary Journal, 182(3), 402-411.

Packer, R. M., Hendricks, A., Tivers, M. S., & Burn, C. C. (2015). Impact of Facial Conformation on Canine Health: Brachycephalic Obstructive Airway Syndrome. PloS one, 10(10), e0137496. http://www.plosone.org/article/metrics/info:doi/10.1371/journal.pone.0137496

Credit picture: I. Horvath

Recommended Comments