Inbreeding, an ideal culprit?

If you ask people on the streets about the main problem of purebred dogs, you can bet the first word coming from their mouth will be "inbreeding". Inbreeding makes dogs ill, inbreeding makes dogs stupid, inbreeding makes dogs aggressive... This oversimplification eludes a large part of what is behind by inbreeding and what is the part taken by inbreeding in the current issue of dog health.

If you ask people on the streets about the main problem of purebred dogs, you can bet the first word coming from their mouth will be "inbreeding". Inbreeding makes dogs ill, inbreeding makes dogs stupid, inbreeding makes dogs aggressive... This oversimplification eludes a large part of what is behind by inbreeding and what is the part taken by inbreeding in the current issue of dog health.

To begin with, inbreeding may have several meanings. It can indeed refer to either a measure of shared ancestry, global reduction of genetic diversity or a given system of mating. Those meanings are of course not independent from each other. Here we will essentially focus on the definition of inbreeding as a measure of shared ancestry, i.e. as the probability that two alleles on a given gene have been inherited from a common ancestor.

Inbreeding also depends on which ancestors you consider, and how far back in earlier generations you will get to find common ancestors. Indeed any individual, including mongrels, can be considered as inbred: it just depends on the number of generations you are looking at. Of course in practice, for a given dog you only know a limited number of ancestral generations. Also, inbreeding occurring 3 generations away will probably impact the dog's health differently than inbreeding occurring 30 generations away. However, It is very important when considering the inbreeding of a given dog, to consider the number of generations on which it has been computed.

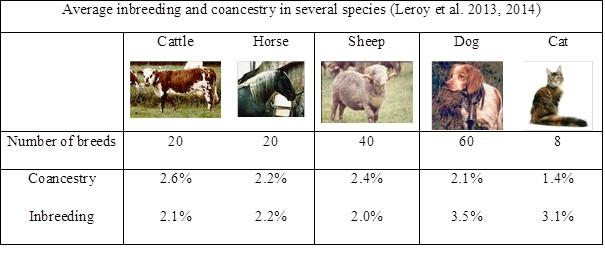

Finally, inbreeding can be considered either at an individual or at a population scale. Considering inbreeding as a measure of shared ancestry, the situation of dog (or cat) breeds are not the same when considering individual (average inbreeding) or population (average coancestry) level. Coancestry corresponds to the level of shared ancestry between two individuals; inbreeding of a given individual being equal to the coancestry of its parents. Averaged over a population, coancestry will correspond to the baseline inbreeding of the breed. If reproducers within the breed are mated randomly, average inbreeding and coancestry are expected to be almost similar, which is for instance not the case of dogs, as illustrated in the following table.

When considering the average genealogical inbreeding coefficients measured on various cattle, horse, sheep, dog or cat breeds raised in France, the inbreeding level appears clearly higher for dogs and cats compared to livestock species, by contrast to average coancestries. This difference is essentially explained by the breeding practice among those two species, and more precisely, by the mating between close-relatives. In fact, in a study on seven different dog breeds, we estimated that around 5% of litters showed a coefficient of inbreeding larger than 12.5% (equivalent to a mating between half sibs). This shows that a large part of inbreeding observed among dog breeds is easily avoidable, by changing some mating practices.

Let´s talk briefly about the effects of inbreeding on dog health. In general, inbreeding consequences are divided into two categories, according to whether the alleles involved have a substantial impact on breed health (i.e. with reference to inherited disorders) or are mildly deleterious (i.e. with reference to inbreeding depression). Inbreeding may be related to the expression of inherited disorders, and more specifically to those having a recessive inheritance mode (the most common one in dogs), as their expression requires that the dog has inherited the allele expressing the disease twice. In that extent, either at population or individual level, higher inbreeding coefficient multiplies the risk of expressing inherited disorders of any kind, especially if that inbreeding is related to a limited number of ancestors (popular sire effect). Note that independently from any form of inbreeding, selection on morphological features deleterious to breed health has a large part of responsibility in the current prevalence of inherited disorders among dog breeds.

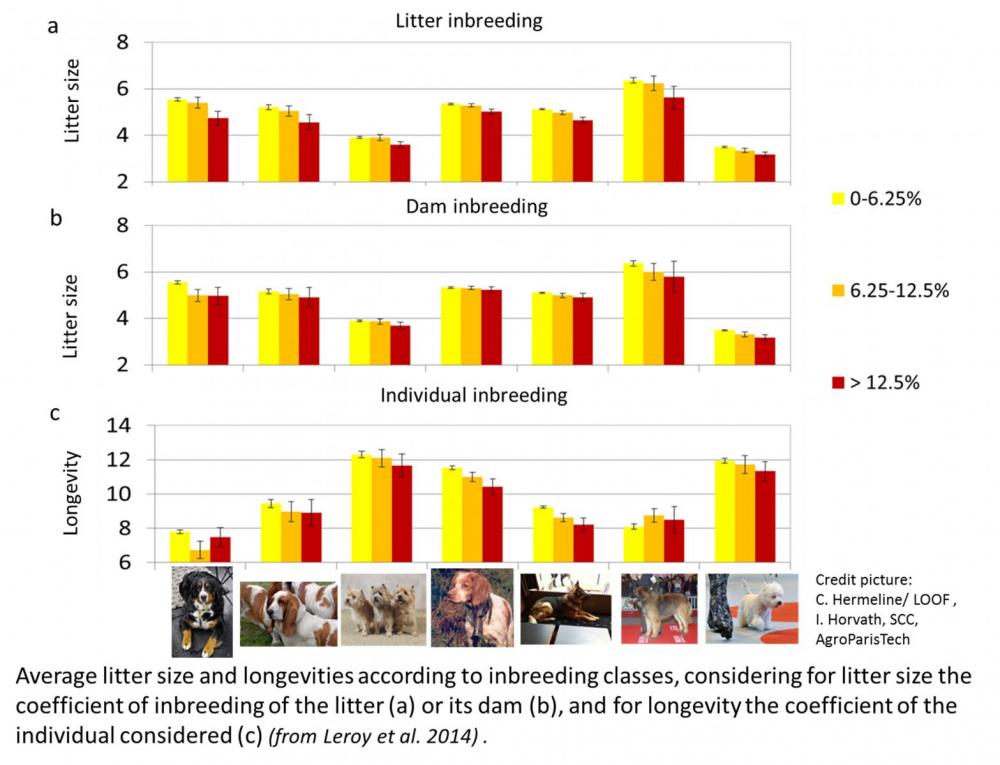

Inbreeding depression refers to the reduction of the mean phenotypic value for traits that can be quantified in one way or another. In livestock species, evidence of inbreeding depression has been showed either for reproduction, growth, conformation or production traits, with an average reduction of 0.14% of the mean of the trait per 1% of inbreeding. This means that for average inbreeding measured by breeds (around 2% according to the previous table) consequences of inbreeding depression are clearly limited. Also the different studies on livestock species have not demonstrated a clear impact of inbreeding on behavioral traits until now. In dogs the consequences of inbreeding on traits related to reproduction, the occurrence of some specific diseases (hip dysplasia), or the longevity (see Institute for Canine Biology webpage) have been reported previously. When considering inbreeding depression, litter size and longevity constitute two interesting life history indicators in relation to their link to prenatal and postnatal survival. As illustrated below, we were clearly able to show the consequence of inbreeding of the litter and its dam on the litter size, as well as impact of individual inbreeding on dog longevity.

On the one hand, if considering the average level of coancestry among dog breeds (around 2%), and summing the impact of both dam and litter inbreeding on litter size (-0.5% each per percent of inbreeding), baseline inbreeding impact only moderately prolificacy in dog, with a reduction of litter size that can be approximated to 2%. On the other hand, in the Britanny Spaniel and German Shepherd Dog for instance, there was an average decrease of longevity of more than 1 year between dogs with inbreeding coefficients <6.25% and those with inbreeding coefficients >12.5%. This illustrates that given the current level of baseline inbreeding (a few percent) reported in most dog breeds, breeders can easily manage inbreeding depression by avoiding mating between close relatives.

So, does inbreeding make dogs ill? Undoubtedly yes, even if it is a predisposing factor, which means that it´s not because your dog is inbred that his health will be compulsorily bad.

Does inbreeding make dogs stupid or aggressive? Until now, we have no proof of that. We may suppose that, as the inbreeding impacts welfare of dog, it might as well affect their behavior. Yet the effect is probably minor, and if you want a culprit for your dog aggressiveness, first blame its environment, i.e. the way he has been raised, which includes yourself.

Should we try to reduce inbreeding increase as far as possible? Clearly yes. Because inbreeding, in its different forms, is one of the key component of the health problems currently occurring in dog breeds. It is not possible to avoid any level of inbreeding, particularly in purebreeding systems. Yet, its extent can be largely minimized through better management practice aiming for instance at reducing close-breeding practice or limiting popular sire effect. There is clear progress to be made in that.

References:

- Leroy G., Mary-Huard T., Verrier E., Danvy S., Charvolin E., Danchin-Burge C. (2013) Methods to estimate effective population size using pedigree data: examples in dog, sheep, cattle and horse. Genetics Selection Evolution 45, 1.

- Leroy G., Vernet E., Pautet M.P., Rognon X. (2013) An insight into population structure and gene flow within pure-bred cats. Journal of Animal Breeding and Genetics 131(1) 53-60.

- Leroy G. (2014) Inbreeding depression in livestock species: review and meta-analysis. Animal Genetics 45(5) 618-628.

- Leroy G., Phocas F., Hedan B., Verrier E., Rognon X. (2014) Inbreeding impact on litter size and survival in selected canine breeds. The Veterinary Journal.

Credit picture: I. Horvath, C. Hermeline/LOOF, SCC, AgroParisTech

Recommended Comments