The sampling effect

I remember in the early months of my PhD to have assisted with a seminar by Raymond Coppinger on dog behaviour. At the beginning of his talk, he told the assembly that all comments and contributions would be welcome, providing the participant did not begin with “my dog did…”. Over the last years, I have begun to think that this comment from Coppinger is the perfect illustration of one the biggest misunderstandings between dog breeders/owner and scientists, that I would call the sampling effect.

Coppinger's meaning was the following: you cannot make a generalization for the whole species, based on the sole example of your own dog. I think this applies not only to behaviour, but also to a lot of traits related to health.

With complex traits, to be able to make generalizations, you need to analyse data on a very large number of dogs… I will take the effect of inbreeding on longevity as an example. How many people have I heard saying “I have known many dogs with high inbreeding that have lived a healthy and long life”?

Well, guess what, they are surely right…

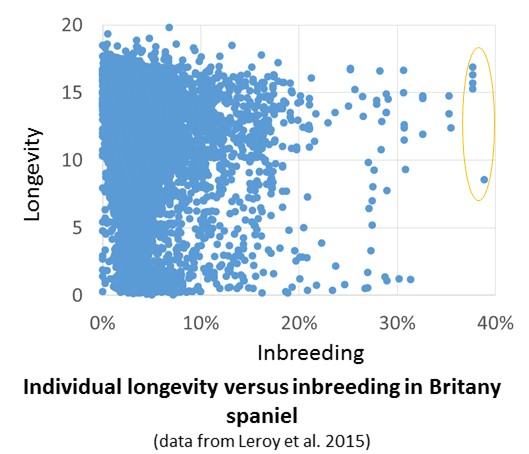

The preceding figure plots the longevity and inbreeding from more than 6,000 Britanny Spaniel (data from Leroy et al. 2015). This plot is not really impressive by itself. If you consider the five dogs on the right side, with inbreeding close to 40% (remembering that 25% corresponds to a mating between full-sibs), one dog died at the age of 9 years, and four died between 15 and 17 years, the average longevity being around 11 years.

So, based on this example, people might conclude that after all, if they can see such inbred dogs live, for most of them, such a long life, then maybe inbreeding does not affect longevity.

Well, guess what, they would be completely wrong…

Wrong, because of the sampling effect, wrong because when considering complex phenomenon such as inbreeding and longevity, you cannot generalize from a small number of examples. You need a lot of data, not on a few dozen… You need at least several hundred, and if possible several thousand.

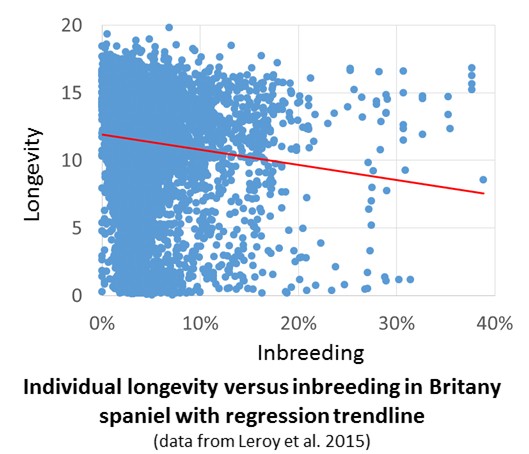

Applying a simple linear regression of inbreeding on longevity to the same data, the impact is clear: for each 10% increase in inbreeding, longevity decreases by about 1 year. More elaborate models, taking into account the specific distribution of data, breeder or animal effect, confirmed this negative impact (Leroy et al. 2015). But the thing is that, as illustrated by the two figures, longevity is affected by a large number of other factors, related to genetics or environment. This is why it requires a lot of dogs to have an estimation of the global effect of inbreeding on the trait. The individuals cited above were inbred and lived relatively long lives. But they must be considered outliers, in this example, and their experience is not enough to impact the findings for the whole population.

By providing this example, my intent is not to criticize the expertise of dog breeders. The message would be more to underline the importance of confronting and sharing one's own experience, to be open to contradictory opinions, and try to gather data and analyse results in all objectivity. In the dog world, we still have a lot of work to do in that extent.

References:

Leroy, G., Phocas, F., Hedan, B., Verrier, E., & Rognon, X. (2015). Inbreeding impact on litter size and survival in selected canine breeds. The Veterinary Journal, 203(1), 74-78.

Donate

Donate

1 Comment

Recommended Comments