Confidentiality and Genetic Testing: more benefits and risks

The parallels between human and dog testing are many, especially in terms of the challenges (and potential) arising from the market move to Direct-to-Consumer testing in both species. I talked about these issues in my presentation to the AVMA conference.

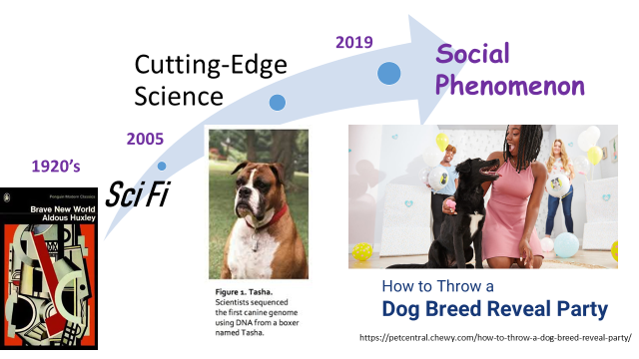

In the slide here, I make the point that in recent years there have been rapid changes, not only in the fantastic and ongoing developments in science and technology, but also in terms of how and why genetic testing is accessed by consumers. And not just in the dog world. For humans as well, genetic testing is very much trending in social media and popular, not simply in medical applications.

An article in Scientific American caught my eye, as it highlights some similar issues that were discussed September 7, 2019, when I addressed the Canadian Kennel Club Board. This article is about sperm banks and how they are admitting they cannot 'guarantee' donor anonymity in the face of services like 23 and Me and Ancestry.com. The basic point, similar in dogs and humans, is that once a sample is submitted for DNA testing, the lab has the material to compare and contrast to other samples they have tested, and to identify related individuals. The labs have the information, or the potential to have it, regardless whether the sample was originally submitted for ancestry testing or a panel of disease tests or one specific test. There is a degree of confidentiality, in that, presumably humans at least can elect not to accept identifying information if the company tells them a relative has been found. Perhaps you can opt out of receiving any information, but in reality many people either are looking for this information, and others do not fully realize what the options mean when they submit a sample.

In the field of human testing, numerous initiatives are looking at ethical concerns in research and for application. One obvious example is where an individual agrees to participate in genetic disease testing, either in a research setting or by consumer choice. Depending on the condition and the results, the tested individual may now know or suspect information about their relatives - relatives who did not sign an informed consent or make the choice to 'know'. It is a complex and challenging situation.

How does this relate to the world of dogs? We have had discussions recently at the 2nd International Meeting of Kennel Clubs in Stockholm, at the 4th International Dog Health Workshop and at the various talks I have given lately. Some kennel clubs, who are expanding or developing health and pedigree linked databases, are suggesting that 'all' registered dogs should have forensic identification and parental verification. Registries have always recognized that dog identification by, e.g. tattoo, and even microchips, are subject to error - accidental or otherwise. When information is going to be part of the permanent record of the dog, accuracy is of extreme importance. However, even if almost all registries demand 'permanent' dog identification, this varies in type (e.g. tattoo, microchip, DNA), potential for errors and, let's face it, the ability of many registries to be absolutely sure that the results are from the specified dog. The Dutch Kennel Club has a phenomenal program for identification of all registered puppies, made possible partly by the limited size of the country. We will try to provide more information on this in another blog or article. The complexities of dog identification have additional ramifications and impacts on health strategies...

A recent paper by Tom Lewis (The impact of incorrectly recorded parentage on inferred genotypes over multiple generations, attached below), geneticist at The KC in the UK, has shown the dangers of designation of 'clear by parentage' when there may be error in the identity of the dog and its ancestors. His work underpins the decision by The KC to limit the clear by parentage to two generations. Presumably, dogs beyond this limited time frame must then be re-tested. Of course, with DNA identification (of all tested dogs) theoretically a much lower error rate could be achieved. (Parentage verification is highly accurate, and there are standards and proficiency testing in place for this type of testing.)

A recent paper by Tom Lewis (The impact of incorrectly recorded parentage on inferred genotypes over multiple generations, attached below), geneticist at The KC in the UK, has shown the dangers of designation of 'clear by parentage' when there may be error in the identity of the dog and its ancestors. His work underpins the decision by The KC to limit the clear by parentage to two generations. Presumably, dogs beyond this limited time frame must then be re-tested. Of course, with DNA identification (of all tested dogs) theoretically a much lower error rate could be achieved. (Parentage verification is highly accurate, and there are standards and proficiency testing in place for this type of testing.)

Tying this back to the concept of confidentiality, the KCs at the International meeting also discussed data privacy concerns around genetic testing and data banks. I won't go into the handling of owner data, de-identification of samples, and numerous other issues, but I will mention one point of discussion that relates to the sperm bank example above. The genetic testing laboratory or researcher or commercial test provider will have the ability - or potential - to detect related individuals by their genetic profiles, whether or not they have owner identification. Not that this means it will be used in a way that should cause concern, but as in the human example, it is perhaps something of which to be aware. Have we been paying enough attention? It seems there is great concern on the human side. This is all complex and confusing; stayed tuned for a coming blog explaining forensic, identification, parentage testing and more.

All of this raises tough issues that will have to be considered by the dog world, as some registries and kennel clubs move towards mandatory DNA identification / parentage testing and others do not. This is another angle where the evolving technology of genetic testing is creating both benefits and challenges.

Resources:

Tom Lewis Impact of Incorrectly Recorded Parentage.pdf

Recommended Comments